I Will Like to Read the Book of Dear America

What Happens Later You Become the 'Most Famous Undocumented Immigrant in America'

In his memoir, the journalist Jose Antonio Vargas attempts to tell the story of his own life while recognizing that he's oftentimes viewed as a voice for millions.

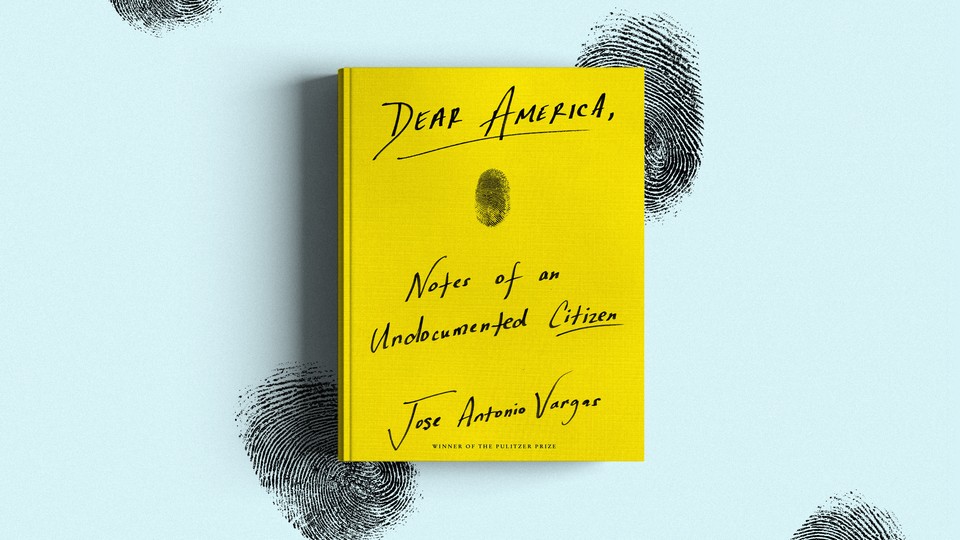

"I swallowed American civilization before I learned how to chew it," recounts Jose Antonio Vargas in his recently released memoir, Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen. Equipped with two dissimilar public-library cards, Vargas gorged on newspapers, magazines, books, music, TV shows, and films that he hoped would teach him—then a sixteen year one-time who discovered that he'd been smuggled from the Philippines into the United States—how to "pass as an American."

Though Vargas was living in the Bay Area with fake residency documents, his mission was to learn a citizen's cultural fluency. Movies in detail fabricated visible the immensity and diverseness of America; they also taught him a cardinal lesson on how the experiences and renderings of a single place can differ, depending on who's telling the story. Subsequently watching four distinct films set in New York City, Vargas marvels, "How can Martin Scorsese'south New York Metropolis be the same as Woody Allen'due south New York City, which is not the same affair as Spike Lee's New York Metropolis and Mike Nichols's New York City?"

Vargas'south heightened attention to the powers of perspective heavily informs his book, which spans the by 25 years of the Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist's life. Dear America serves equally the most comprehensive follow-up to three works in particular: Vargas's 2011 New York Times Magazine essay, "My Life equally an Undocumented Immigrant"; his 2012 Time embrace story, "Not Legal Not Leaving"; and his 2013 film, Documented. More than notably, the book is Vargas's starting time long-form piece of writing that tries, through the use of vignettes, to distinguish his individual self from his public persona. Both a journalist and an activist who founded the nonprofit Define American, Vargas notes that he's often regarded as the "most famous undocumented immigrant in America." In other words, he's aware that his life story volition never exist entirely read every bit only his own; still, that doesn't stop him from attempting to tell that story through memoir—a genre that requires an extended introspection of the self.

In a directly address to his readers early on in Dear America, Vargas situates his tale as beingness "simply … one of an estimated 11 million here in the United States." This determination to pull away from a single immigration narrative is consequent with how Vargas has approached the subject in the past every bit a reporter. Though the memoir focuses on his story, it is divided into three sections named for three experiences that he argues all undocumented people share: "Lying," "Passing," and "Hiding." The book seems to follow in the footsteps of Vargas'south literary idol James Baldwin, who, upon returning to the U.Due south. from France in the midst of the civil-rights movement, recognized the part he could play.

"I didn't think of myself every bit a public speaker, or every bit a spokesman, but I knew I could become a story past the editor'southward desk," Baldwin said in a 1984 interview with The Paris Review. "And once you realize that you can do something, it would be difficult to alive with yourself if you didn't practice it." Whether Vargas feels the depth of that responsibleness to a larger community (as Baldwin describes) is maybe unknowable. Merely the selection—to "practise something"—may not always be a single person's to make, as a young man undocumented friend of Vargas's points out in Dear America: "In our motility, you come up out for yourself, and yous come out for other people." This was particularly true for Vargas in 2011 and for the 35 other undocumented people who joined him on the historic June 2012 cover of Fourth dimension.

As others take observed, Honey America recapitulates experiences the author has written about elsewhere, offset with the morning a 12-year-onetime Vargas is awoken past his mother. He's hurriedly sent in a cab to the airdrome and flies to the U.S., where he's taken in by family members who've settled in Northern California. The early on capacity describe Vargas'southward delight at eating Neapolitan ice cream for the starting time time, his acculturation of American slang, and how he came to sympathise the U.S. every bit a place of racial plurality and hyphenated identities. He describes once more how, while applying for a driver's let at the age of 16, he learns that his dark-green card is fake and that the lies that brought him into the country were now his burden to bear. In a department virtually what prompted his conclusion to come out as gay to his high-school classmates and his grandparents, Vargas explains how conveying one hush-hush was hard enough.

The memoir grade, however, allows for pockets of fresh details, including a chapter on what it ways to be Filipino—a group, Vargas writes, that seems to "fit everywhere and nowhere at all," particularly in national discussions virtually clearing, which overwhelmingly focus on the Latinx community. In the chapter "Mexican José and Filipino Jose," Vargas writes about California's Suggestion 187 from 1994 and how even and so, "whenever 'illegals' were brought up in the news … the focus was on Latinos and Hispanics, specifically Mexicans." And subsequently, a classmate who had asked Vargas nearly his green carte du jour points out: "I guess y'all don't have to worry near your greenish card … Your name is Jose, but you look Asian."

Vargas's candid prose is inviting to readers who are new to his story, as well as to those who might be unfamiliar with the complexities of U.S. immigration policy. The author covers the precedents and ramifications of several measures and laws, including the Rescission Deed of 1946, Operation Gatekeeper, the 1996 Illegal Clearing Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, and the 1996 Antiterrorism and Constructive Expiry Penalty Act. The 1996 laws, Vargas notes, "made it easier to criminalize and deport all immigrants, documented and undocumented, and made information technology harder for undocumented immigrants like me to adjust our condition and 'get legal.'" From endless angles, the memoir illustrates why it's nearly impossible for Vargas—and incalculable others—to "go in line" and become an American citizen. (As he emphatically points out multiple times, there is no such "line.")

Vargas'southward attempt to answer all relevant questions—roofing every possible base of operations, taking into account the varied experiences and precarious statuses of the millions living without documents in the U.S.—is where the volume gets bogged down. The memoir, as it veers into reportage, loses Vargas in the multitudes. His justified exhaustion at having to continually explicate his and others' predicaments to people across the political spectrum is palpable. Late in Dear America, for instance, he expresses his frustration with some of his almost acerbic critics: other activists who've outright told him that he'southward too successful to exist the media'due south face of the immigrant-rights movement. "I exchanged a life of passing as an American and a U.South. citizen so I could piece of work for a life of constantly claiming my privilege so I could be in the progressive activist globe," Vargas writes in a sobering passage.

For many readers like myself who grew up undocumented and who have been post-obit Vargas'southward trajectory since his 2011 essay, seeing the verbal means in which his story diverges from our own is the crux of the memoir. His America, equally others have pointed out, is one of unusual advantages: He was lucky plenty to attend "a relatively wealthy school in a community of privilege," a community where people with connections, money, and access to lawyers protected and allowed him to build a life for himself.

Committed to freeing himself from the many lies he had to tell to protect his identity, Vargas is forthright and explicit in Beloved America about the doors that were opened for him. In the affiliate "White People," for example, he explains how certain friends helped him obtain a driver's license. That piece of identification immune him to accept a summertime internship, then a ii-year internship, and then a job at The Washington Mail—the newspaper where he earned his Pulitzer as part of a team that covered the 2007 Virginia Tech massacre. His is an undocumented America of white-collar work and white-neckband spaces. In a startling passage about being interviewed past Megyn Kelly on TV, Vargas observes how "as a group of people, Kelly calls usa 'illegals,'" but "in person, to my face, she always refers to me as undocumented."

"Memoirists shouldn't exaggerate the about gruesome aspects of their lives," explains Mary Karr in an interview with The Paris Review. "You have to normalize the incredible." Dear America seeks to lay bare Vargas's unadulterated truth, which is that even he—with all of his accomplishments, accolades, and associations—is caught up in the labyrinthine U.S. immigration laws without recourse. He was, after all, three months also old to qualify for the limited protections afforded by the Deferred Activeness for Childhood Arrivals program, a 2012 policy whose age brake essentially created a generational divide betwixt undocumented people.

Vargas's lack of temporary legal protection, in fact, is what results in his existence detained subsequently a acuity welcoming Cardinal American refugees at the McAllen, Texas, border in the summer of 2014. "I exercise not know where I will exist when you read this book," Vargas writes in Love America'due south prologue. "I don't know when the government will file my [Notice to Appear] and bear me from the country I consider my abode." In this moment, the memoir inadvertently asks readers to consider again the estimated 11 million undocumented people in America and wonder how many, like Vargas, might be disregarded in conversations effectually the revoking of DACA and the Deferred Action for Parents of Americans programme, or bills like the DREAM Act, whose various iterations have also included historic period restrictions.

Dear America is significant for its expression of individual difference inside the overlapping experiences of undocumented people. As the memoir's research shows, Vargas'southward perspective is merely ane contribution to an evolving narrative and long-continuing history of clearing. It is the individual details of his story, though, that further reveal the breadth of undocumented America. "I'thou a relative newcomer," Vargas confesses in a moment of intimacy that reminds readers of Dear America's epistolary foregrounding. In moments like this one, the solitary vocalization of Vargas arrives as a letter in the reader'due south easily, from a sender, we remember, with no return accost to call home.

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2018/10/dear-america-jose-antonio-vargas-memoir-review/573013/

Postar um comentário for "I Will Like to Read the Book of Dear America"